Warning: the following contains spoilers in the fourth paragraph.

96 year-old Portuguese auteur Manoel de Oliveira -- that really says it all doesn't it -- is the world's oldest active filmmaker and is the only director to begin his career during the silent era. Oliveira has been particularly active since the mid-1970s, having made approximately one film per year in the period since. Yet, what is more remarkable than the director's age or even his late-career productivity is the consistent high quality of his work: no European filmmaker has made more great films in the past fifteen years than Oliveira (and were not such a large number of his films from the 1980s still unavailable, one could perhaps push that date back even further). For arguments sake, one could name Abraham's Valley (1993), The Convent (1995), Party (1996), Voyage to the Beginning of the World (1997), The Letter (1999), I'm Going Home (2001) and A Talking Picture (2003), and one would have one of the world's most autobiographical and formally adventurous cinemas without even naming such agreed upon masterpieces as No, or the Vainglory of Command (1990), Inquietude (1998) and The Uncertainty Principle (2002), which like the earlier films, remain unavailable to US audiences.

Oliveira's latest feature, Magic Mirror (Espelho Magico, 2005) -- if one doesn't count the picture he is currently shooting with Bulle Ogier and Michel Piccoli -- has likewise not yet secured US distribution, and may remain without a distributor into the immediate future. For one, Oliveira hardly rates as a household name, despite the brilliance of his body of work; and two, the Portuguese master remains one of the international art house scene's most challenging auteurs.

Magic Mirror continues many of the master's long-held formal and thematic preoccupations: namely, mortality, the relationship between film and theatre and the moral status of wealth. Similarly, Oliveira utilizes the gorgeous Leonor Silveira (a mere 60 years his younger) as a proxy for his person, just as he did with his supreme achievement of the past decade-and-a-half, Abraham's Valley. In this case, Silveira plays the devout Alfreda, whose childlessness compels her to fantasize about seeing the Virgin Mother, particularly after she is told that Mary was the product of a wealthy family: she too was born into enormous wealth (as was Oliveira himself), and hopes above all else to talk to the woman, presumably in hopes of unlocking the mysteries of both the Christ child's miraculous birth and also the Judean woman's relative fortune -- thereby settling the issue of the wealthy's difficult path to salvation that one finds in Christian doctrine.

Significantly, Alfreda never finds the answers she seeks, just as one might suspect Oliveira himself has not found sufficient answers to the questions of God's existence (The Convent and Party seem to treat this subject most directly; and in a similar fashion, one might see Ricardo Trepa's freed criminal and his prison companion as exemplars of a protest theodicy of sorts, particularly with the latter's instance that he is animated by hate) and second, to means by which he might reconcile his social position and the social imperatives of his art -- again Abraham's Valley is the finest treatment of this subject. Still, Oliveira does happen to save one unprecedented moment of genuine magic for the end: the narrative continues after Alfreda passes on, without the answers, compellingly giving us Oliveira's own conceptualization of life after his own death. Here, we see a newly-minted couple, a smiling young child and the continuation of the estate (that houses much of the drama) accompanied by the joyous lilt of the score. Life continues, unabated, in all its richness.

In this concluding passage, Oliveira offers what could have been a wonderful epithet to his career -- just as I'm Going Home could have been one of the most profound final films ever made -- were he not already at work on something new. Whether this film rates with the others listed above (it most likely does not, though it is by no means minor within the context of European art cinema) the fact that we still have Oliveira and that he is still as prolific as ever is itself cause for celebration.

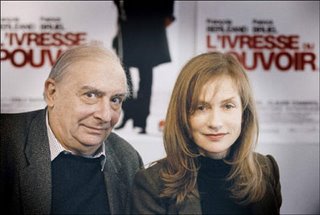

Also without US distribution at present, is the latest from French New Wave auteur Claude Chabrol, A Comedy of Power (L'Ivresse du pouvoir). While Chabrol is more known in the broader culture and film world as a whole, the quality of his work is far less consistent than is Oliveira's. The French director's latest effort is middling to be sure, even if it begins with an absolutely brilliant opening sequence: in one unbroken take, Chabrol follows a corporate criminal from the heights of his suburban Paris office to the street where he is apprehended and charged with defrauding shareholders. From this bravura opening shot, Chabrol establishes a spatial logic that he maintains for much of the film -- namely that power relationships are established in terms of distance from the ground. The film's conspiring CEO's occupy the upper floors of glass and steel behemoths, while the film's crusading magistrate, Isabella Huppert, operates far closer to ground level. Of course, the point is to get the big-wigs out of their towers, just as it is for Huppert to herself ascend. Conflict, on the other hand, is the result of shared heights, such as Huppert and her cause-weary husband, as well as with the fellow female magistrate next to whom they (the conspiring Gaullist power-brokers -- very much Lang territory -- that is) place Huppert, in the hope that they will take each other down.

Together, these threads suggest a narrative critical of bourgeois greed and the will to destroy those with money -- an interesting critique by a director like Chabrol in a nation like France, certainly. However, Chabrol's narrative soon loses the focus of its first part, en route to one of the least satisfying endings of the director's recent career, which is doubly disappointing considering that the spatial logic is for time, the most rigorous of any of Chabrol's films since Le Boucher (1970). Yet even in this system, Chabrol doesn't complete the promise of what at first appears to be genuine mastery.